Last week,

wrote “The Classics in the Slums” about poor people reading the great works of literature. He also quotes great stories of desperately poor 19th century British miners being transformed by reading Shakespeare and co.I agree. I read Plato sitting on a barstool while working as a bouncer. That was good for me in ways I have trouble articulating.

We all have this inkling these works are “important.” When we try to explain why, though, it comes across as impractical moralizing: “You simply mustn’t forget art and feelings!”

It’s like when you tell your kid “it’s not important if you win, it’s how you play the game.” That’s probably true, right? But it’s suddenly hard to explain to a child—your child! Especially when wiping their tears after they lose. Here, our unspoken moral intuitions are put to the test.

Telling poor people to read feels equally uncouth. Tossing a Dickens novel into a Dickensian home feels, um, cruel. The more practical side of us thinks, “Sure, sure… Oliver Twist and all that. But you should probably just focus on what’s making you poor?”

That’s unfortunate because this attitude, in the long run, makes our kids into sore losers and keeps poor people poor.

I read "The Dictator's Handbook," 10 years ago, and I’ll never forget one thing: tyrannical governments keep their populations from rising against them by (get this) funding only STEM. You can just follow the money: the more tyrannical the country, the less they promote the humanities.

With no emphasis on humanities, the unwashed masses 1) can't conceptualize how anything could be any different, and 2) their children don’t inherit a wisdom tradition, which could provide them the moral stability to be a threat. As an added bonus, the intelligent subset of the subjugated population may still use their brain power, but only to make the tyranny more efficient.

Maybe you’d think, “There is no smoky room of conspirators stopping poor people from reading Wordsworth.” And, yes, that’s true. But, conspiracy happens mostly without evil cabals, a-la, "Manufacturing Consent.” Chomsky (often very wrong IMO, but we can borrow his data) shows that if you follow the money, the establishment is always going to lubricate behaviors that protect their power and ignore things that don’t. Yes, sometimes that's a conscious, mustache-twirling behavior. Most of the time, it's just the way the water flows.

At the very least, that tells us establishment power acts as if reading great works is a threat to their rule. So, you can just reason backward: to empower the poor, read great books.

Personally, I wouldn’t be here if my great great Uncle hadn’t broken his leg one summer, read the classics, and altered the entire course of my family history.

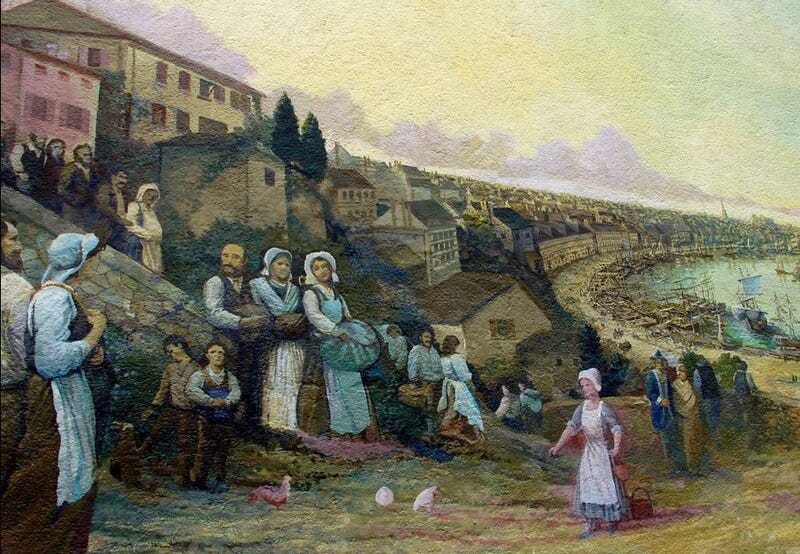

Around the founding of the United States, my ancestors lived in Canada. The English won and drove out my people, the French. They were forced way down south to Louisiana.

My other ancestors lived in a town called Meaux, France. I visited there with my brother a few years ago—it’s a beautiful little town with a massive stone cathedral in the center. My great, great, great grandfather lived there. He was a well-educated boy from a good family. He went to college and read the great books. Then, he came home and started a family.

But one day, he heard word of these other French people—Cajuns!—settling in Louisiana. A land of new opportunity! He got on a boat, left his family behind, and went to the new frontier. He and his new family quickly became the richest people in Louisiana. They owned every trading post in the state. He didn’t bother to have his boys read any great books—they just worked in his trading posts, raking in piles of money.

It’s Meaux family lore that he used to smoke $100 bills (my grandma used to tell me and my cousins that, anyway). I hope that was fun for him while it lasted. Because, of course, within two generations, all that wisdom and wealth was gone.

Then, my great great uncle Claude was born, poor beyond belief. No one in the family could even read anymore (amazingly). All the boys were expected to work the farm, so books were not a priority. But, Claude broke his leg one summer. He had time to read the dusty classics of his grandfather.

As he read (not studied, but truly absorbed the texts), he developed a gravitas about him (the type Ted Gioia got after reading for decades). By the time he was in his 40s, people would travel from all over the state to listen to him speak. He passed on this tradition to his two sons, my great uncle Claude and my great uncle Junior. They're still alive, near their hundreds, somewhere in the swamps of Louisiana.

Those two were powerful influences on my grandfather, Wilford. He worked for an early competitor of Walmart. More than anything, he wanted his kids to have a better life than him. He even bought them a set of encyclopedias (a massive investment at the time).

These days, my uncles do high-level work in Louisiana and raised good families of their own. My mother carried on the tradition of her father, too, and my two brothers and I have more opportunities than our dirt-farming ancestors could have possibly imagined.

By reading and appreciating the classics three generations ago, Claude redeemed what was lost by a single impulsive ancestor. Probably every person reading this can look back and find one ancestor on whose shoulders they rest. Without those singular people, our culture descends into impatience and madness. A culture of non-readers (which we are becoming) is at best, accumulating a single generation of wealth, leaving nothing lasting for our kids, forever enslaving them to a lack of perspective. Hopefully, an uncle Claude will come along to redeem them.

This is obviously not a comprehensive list of reasons to read great books. I’m not even addressing the main reason: because they are great. But, hopefully this gives a few words to our intuitions, to respond to cynicism. Cynicism pretends to raise us above paltry sentimentality, but it really destroys something precious that we don't understand.

If you're poor, reading the classics might not make your financial position better in your lifetime. People don’t associate wealth with reading classics because that’s not why you should read them. But, the numbers suggest they are associated—on a long enough timeline. It’ll at least enrich you in other ways. And, it might establish some wisdom in your lineage that will rescue them from an endless cycle of short-term gratification.

It's so obviously what we ought to be doing that it is almost our duty.

Wow, great writing! Thanks for sharing.

This is poignant in a way that feels like remembering something I had forgotten. The true measure of good teaching! Thanks for sharing about your family. :)