Long ago, my brother and I played The Sims on a computer running Windows 95.

We built fancy houses, installed fire alarms, and laughed at the foibles of the babbling virtual people. When he went to bed, I even dared to flirt with the ridiculously seductive Bella Goth:

One day, he taught me the “Rosebud;!” cheat code like it was a drug deal. “This will get you unlimited money, man. There’s no catch, I swear.”

Of course, the catch was that it drained the game of all meaning.

Unlimited resources transform complex virtual lives into pointless colored pixels. Realizing this at the age of 12 gave me PTSD.

Unfortunately, fun in The Sims does not correspond with how many simoleons you have in the bank. Although your explicit goal is accumulating more money, status, and fuller “spirit bars,” the good time is in the upward struggle. Or… well, not.

This cosmic wisdom has been around (at least) since the ‘90s. Despite that, if real life had a “Rosebud;!” cheat code, you would smash it without blinking an eye. I know I would.

Why?

To answer that, let’s return to a time even before the ‘90s. The Ancient Romans used to tell a creation story that was remarkably similar to The Sims. Let’s make a pretentious comparison, shall we?

At the dawn of time, a girl named “Sorge” (which translates to “Concern” in German, from Heidegger’s translation of the original Latin) skipped along a river.

She squatted at the bank to make a figurine out of clay. She cackled with delight at her creation, posing the legs and using her own voice to make it talk.

After a while, she wished it had its own spirit. Maybe then it would do something surprising…. She called for Jupiter.

Jupiter, God of Spirit, imbued the doll with life. However, he demanded the creature be given to him.

Then, the Earth insisted she get the precious doll, which was made from her clay.

To the doll, the gods’ argument was an apocalyptic light show. Sorge alone protected him through the calamity. As the cosmos shook, they lost sight of what dangerous attention they might attract….

From the shadows, Saturn, subtle as a snake, spoke, “Since you, Jupiter, have given it spirit, you will receive the spirit upon death. Since you, Earth, have given it a body, you will receive the body upon death.

“Since Sorge crafted the creature with care, it will be hers all its life. It will be called Human (homo) after Earth (humus).”

This was originally written by the Roman author Hyginus, then translated by the philosopher Heidegger, and then spiced up by me.

Sorge, or “concern,” is at the core of being human. Does this mean anything beyond being a cute story?

Let’s pull apart the meaning of the German word Sorge. It’s something like “concern.” Breaking that word down, it’s both “care” and “suffering.”

You might remember from an Alan Watts lecture (or something) that the first Buddhist principle is “life is suffering.” But, the concept of “suffering” has changed, like how the word “mad” has changed from “insane” to the more American “angry.” “Life is suffering” doesn’t mean “life is pain,” as most people interpret it. Suffering in Buddhism means “struggling with.”

Life is to be contended with because you care.

Without that kind of suffering, playing The Sims is no fun.

State-of-the-art polygonal graphics (Jupiter) are not the point of the game. Nor is it all 16MB of RAM (Earth). The point of the game is the spirit to sit down and suffer (Sorge). Relatable.

Entering “Rosebud;!” eliminates the need for Sorge. Once she’s gone, the party's over. Who “cares” (literally)?

The developers obviously had an intuition about this because they named the cheat “Rosebud” from the movie “Citizen Kane.” Rosebud symbolizes that Kane’s wealth, power, and success are worthless compared to his simple childhood concerns.

He felt the same existential dread I experienced typing “Rosebud” into my Windows 95 computer. We deserve equal pity.

A powerful story. One that makes you “care” about the main character, Kane. And me.

Exactly how do storytellers and video game developers make us “care” about fictional characters, anyway?

One thing I’ve noticed is that video games sometimes start with a creation myth, similar to the one I laid out above. For example, The Legend of Zelda games usually begin with a story of how the world was formed:

Unconsciously, the game is telling me, “This is the beginning of time. In this void, there are no struggles. Now, let me introduce you to a particular character’s struggles. Give them your ‘care’ so you can play.”

Even if you later rage-throw your controller into the TV screen, you know it is all for the good of play. You eagerly accept this devil’s bargain as the soft piano of “Tears of the Kingdom” begins. Within the shrine of the game, suffering is acceptable.

Stories (video games) serve many functions, but an important one is to remind us that our limitations and resulting suffering are what make our lives worth living.

I hear you screaming, “That’s not why people play games! People just want to be entertained!”

And to that, I would say: what do you mean by entertained? We use that word as if it means the activity is frivolous. But, the instinct for entertainment is part of our survival instinct – otherwise, it wouldn’t still be around. The entertainable cavemen were more likely to survive.

What exactly is the survival value of entertainment?

It’s all about knowing “the vibe.” If mythos is how you “feel” the rhythm of the music, logos is dry musical theory. Being good at one does not directly translate to the other.

In other words, you can be a master of musical theory and still dance like Elaine from Seinfeld.

But dancing is not just the ability to impress at a wedding. Remember, Sorge’s a little girl — she wants to play and dance. She cares.

That girl’s “care” is what animates you. And, it’s the same care that you animate your Sim through you. Without that, you are nothing more than the clay from which you're molded. The Sim is nothing more than pointless pixels.

She’s what the misunderstood Heidegger called “Dasein.” She’s the force of anti-entropy that denies the second law of thermodynamics (everything seeks greater entropy).

Despite learning this lesson when Windows 95 was a thing, I still stupidly long for a real-life “Rosebud;!” cheat code for more money, status, and fame, refusing to understand that it would end the whole play.

Now I hear you saying: “It’s easy to claim that limitations give life meaning when you’re just playing a dumb game. Real life is full of real suffering. More money would fix that in my case.”

Fair enough, strawman I made up. I’m not here to convince you that your suffering is for some greater meaning. Nobody can “convince” anyone to fully fall in love with their limitations. That’s done, if at all, beyond the scope of logic. Otherwise, it usually comes across as thoughtless. It’s like suggesting cancer “happens for a reason.” I mean, c’mon.

Imbuing meaning to tragedy is the realm of storytelling (mythos) – probably not through a shallow, philosophical essay like this.

That’s exactly why I loved the interactive novel “House of Leaves.” Here’s an example of some of the text from the book:

Because you have to turn the book upside down, tilted, and sideways, reading it makes you feel even more part of the myth unfolding. Then, you are introduced to a character who introduces you to a fictional character within his world, who introduces you to a fictional character within that world, and so on. As you travel down these narrative layers (like “Inception”), you begin to feel yourself even more as not the passive reader but as the “top layer” of the narrative. I’m not exaggerating: reading this novel made me feel I was going insane – in a good way.

Adding layers of myth and slowly peeling them back reminds you that your life is a narrative myth, too.

That’s how you felt about your world before being indoctrinated by the “rational materialism” myth, which pretends it's not a myth. That myth, by the way, is the one that suggests “Rosebud;!” would solve all my problems. If the world is just material, then more is better, right?

No. Life is maddening chaos. So is that damn book. It made me suffer. But stories — even the ones in The Sims — attempt to show a path back to the light. Back to care.

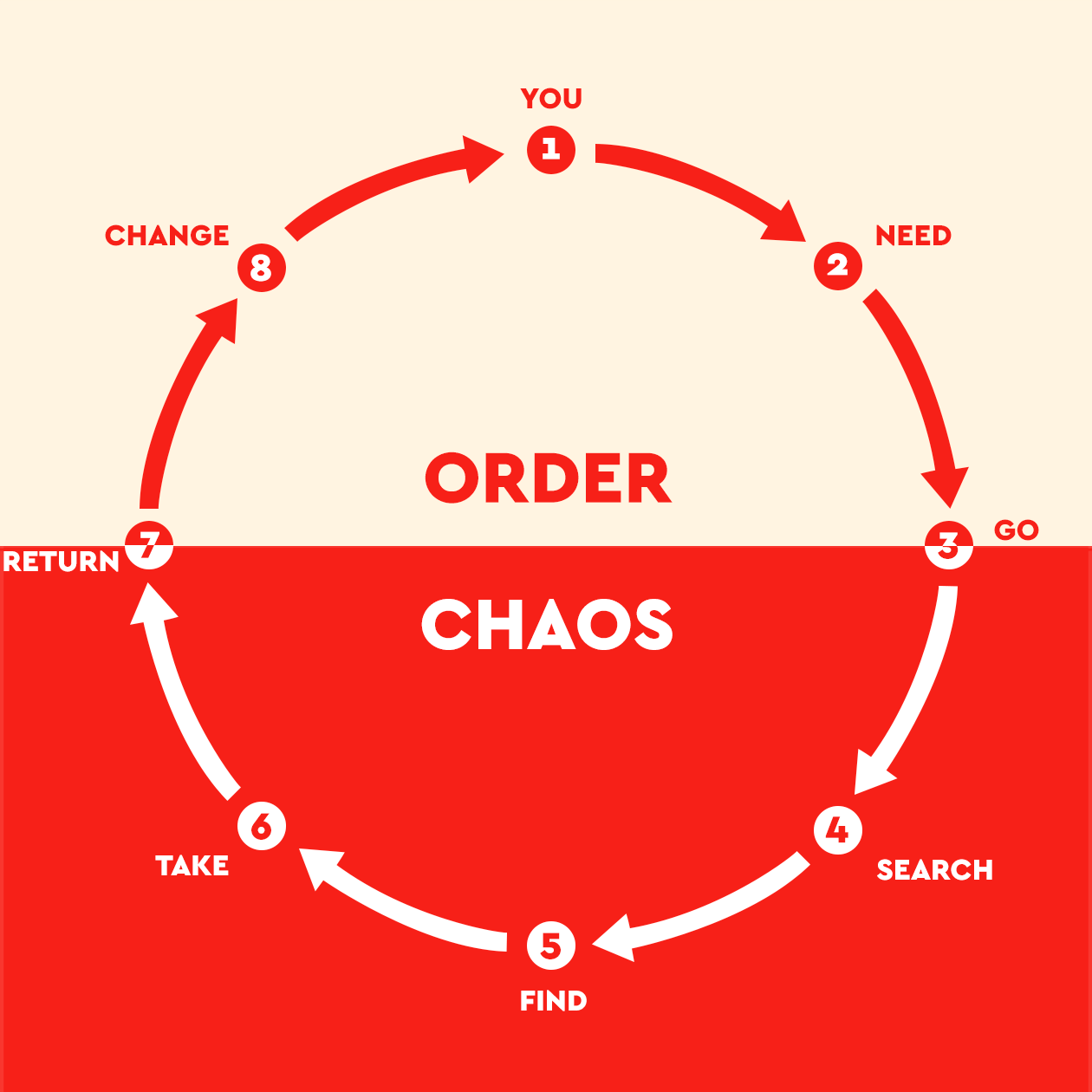

This is how narrative works.

What did I gain by spinning on this cosmic wheel (time is a flat circle)? The beauty of a story. Of course, you could say, “F*ck The Sims and bail,” but then I wouldn’t know about Bella Goth. How could I live without her unspeakable grace?

Sorge has no story without you. That’s why she’s with you your whole life (as Saturn said).

But she doesn’t want to be overwhelmed with impossible challenges. Nor does she want to design virtual houses with unlimited money. She wants to suffer at an optimal rate. This is called flow, which is technically what happens when we play.

Hang on, this whole thing is coming full circle.

What’s satisfying about playing The Sims is the joy of Sorge (God, the universe, higher power, whatever) wiggling herself through the knots of being through the Sims, finding the poetry and humor of the solutions.

That’s also everything good about real life.

For inspiration, watch this YouTuber, ambiguousamphibian, play The Sims in the most hilarious way possible. Is he “winning” the game? Is it productive? Is he optimizing ROI (or whatever)?

Who cares? It’s fun.

Thanks for reading,

Taylor

I love the story about the Sims. Reminds me of the story I wrote about my experience in GTA when I was given a trillion dollars.

I also love that you dug into the etymology of Sorge and what suffering truly means. I think there is a microcosm of meaning in just that. In our culture, we connote suffering with negative emotions, and so we avoid it at all costs. That's true in developing countries, but in America, we have the opposite problem-- too much ease. People are unwilling to suffer, to delay gratification, to practice discipline. We see it in their eating habits, the way they let their dogs get away with everything, the way they let their children do the same.

I would argue that games are not just about limitations and suffering, but about the eternal struggle to overcome them. As we play the game more, we get more experience, develop new powers, get better equipment, and this makes those earlier obstacles conquerable. But this only presents us with bigger challenges. But that's great.

In life, we don't want to just worry about the little problems (getting enough food, making enough money), but we want to spend our time worrying about big problems (how to create great art, alleviate the suffering of others, make the world a better place). Perhaps that is the "greater meaning" of suffering, to provide the resistance we need to grow stronger.

Or perhaps, it's all just for fun, as we play the game of life.

Reminds me of Gordon Gecko in the movie “Wall Street”, who said, “Greed is good.”