What compels humanity to make all these strange marks?

Thousands of years ago, the Hebrews found themselves displaced, roaming the earth in search of a homeland. This led to the development of the first alphabetic writing system.

Before the Hebrews, no other civilization found it necessary to record so much information. They got by just fine with “picograms.” Their environment was their memory's tapestry. You didn’t have books; the mountain was where the gods lived, the stream was where you were baptized, and the tree was where you met the goddess.

The ability to communicate through the more complex alphabetic written language allowed the Hebrews to transcend their physical surroundings and conceive abstract ideas. To them, “home” wasn’t made of soil; it was in the Torah – the hypothetical future of the “promised land.” A radical idea at the time.

The book itself became a vast, interconnected hyper landscape. Here’s a visualization of all 63,779 internal connections (references to other parts) of the Bible. Seen like this, it is the beginning of an “inter-net.”

The Hebrews might not have fully realized the potential of their invention. Still, the written language has since transformed human civilization in countless ways (written laws, battle plans, bank records, Instagram, sexting, and this article, for example).

The development of written language was like Prometheus bringing fire to humanity: it is powerful but caused a lot of collective pain. Mostly, this pain runs in the back of our minds like the hum of a forgotten box fan, only popping into our awareness in cases of addiction or existential dread.

We should understand AI (large language models) as the next great leap forward in human language, similar in scale to the world-shaking power the Hebrews stumbled upon.

We can even understand what to expect from AI in the coming decades by understanding what writing did to humanity.

When they severed earth from sky

In pre-literate ancient Greece, people called “rhapsodes” would wander around their land, telling stories and myths about heroes and landscapes with lyricism and poetry.

They memorized the fine details of hundreds of stories. How do they do that?

“Memory palaces” work so well to help you remember the names and dates for your English test because you evolved to memorize landscapes, not lists. That’s why people talk with their hands – as if orchestrating an army of ideas on the grassland of their minds. It’s also why you know every lyric to “All Star,” but can’t remember what you ate for lunch the day before yesterday.

“The Illiad” and “The Odyssey” are among the first written transcriptions of these oral traditions, and both contain echoes of this lyricism. The verses beg to be read aloud (in their original Greek). But even in English, you can feel the rhythm through artifacts like the repetition of particular phrases like "πολυφλοίσβοιο θαλάσσης,” often translated as "wine-dark sea" or "wine-dark deep," and it frequently repeats throughout both stories.

But, as writing spread, these storytellers, bards, and rhapsodies who, ironically, gave rise to these epic poems, were made irrelevant. With a more permanent way to record events, there is no reason to have people dedicated to memorizing them.

Even Socrates himself (not literate) complained about the advent of writing, feeling that people wouldn’t remember anything:

"If men learn this, it will implant forgetfulness in their souls; they will cease to exercise memory because they rely on that which is written, calling things to remembrance no longer from within themselves, but by means of external marks." — Socrates, Phaedrus, 274c-275b

Yes, writing gave people incredible power, but the emotional and tactical loss was devastating.

For example, when the Europeans landed in the New World, Native Americans called their strange written pages “talking leaves.” The dark marks on the leaflike pages seemed to be able to speak to those who knew their secrets.

The introduction of “talking leaves” to natives suddenly disrupted this vital link to the spirits of the land, effectively dissipating their "magic,” which was their embodied connection to their particular landscape.

They never recovered.

"The introduction of the alphabet into the indigenous, oral cultures of North America was at once a forceful intrusion of a foreign influence and a subtle, yet profound, restructuring of the native sensibility, eventually contributing to a widespread disorientation and loss of meaning." — Spell of the Sensuous, David Abram, p. 210

The raw power of abstraction cannot be resisted, even if being directly connected to the landscape may be better for emotional well-being.

You and I have engaged with writing since we were young, so we have trouble imagining a world without it. But our brains still use the same cognitive abilities once dedicated to mapping physical landscapes to navigate the conceptual realms introduced by writing. We feel this dislocation somewhere deep in our bones. Physical places became… mundane and dead, while abstract places grew in power. We forgot the purpose of beauty.

Writing has abstracted us away from what it felt like to be a rhapsody in Greece or a church-builder in the middle ages.

The modern world feels mundane, doesn’t it? Buildings are glass and metal boxes. Cities are concrete labyrinths. You don’t have a sense of mythic meaning, do you?

Can you remember a time when you did?

Childhood myth-making

A hidden treasure is packed into our hazy childhood memories.

Something that allows us to understand more viscerally what humanity was like before modern times.

In “The Origin and History of Consciousness,” Erich Neumann, who was Carl Jung’s student, explains that the development of my early consciousness (childhood) mirrors the formation of early human consciousness.

"The great individual mythological ideas and symbols of the child are thus seen to be archetypal, and in their general structure they correspond to the great collective ideas and symbols of human history. In this way, ontogenetic development, which is the fate of the individual, can be seen in its archetypal connection with the phylogenetic development which is the fate of the species" —Neumann, p. 8

As a kid, I would go camping in the summer, and without thinking, groups of boys formed tribes and roamed the landscape.

The pond with the rope swing was where we bullied each other to jump in (learning courage), the hill of the official footpath was where we talked about secrets (we thought) the adults didn’t know, the cafeteria was supposedly “haunted” by the ghost of a boy who had died years back. The old live oak tree in the valley was “the underworld.” We were too afraid to visit at night (unless on a dare).

I can’t remember what I ate for dinner yesterday, but I can still remember the fine details of these locations: the worn-in dirt footpaths, the climbable curve of a branch, the smell of overcooked chicken, the hill the sun set on in summer.

A kid named Christian (who, incidentally, passed away from his type 1 diabetes that year) told us that he saw “Candyman” coming out of the woods, covered in honey and swarming bees, so he shot him through his hand with his BB gun. Something about that seems particularly salient, even to me now.

These parallel realms of “other,” “underworld,” and “haunted” felt exactly as real as to us our warm bedrooms back home — certainly more real than abstract letters and numbers. School had not drowned our imaginations just yet.

Where does this ability for meaning-making go?

As we grow older, we learn to navigate the world of abstraction more efficiently. A world of symbols, language, and complex landscapes of ideas replaces the mythic landscapes of our childhoods.

Just as the written language disconnected us from our ancestors' physical landscapes and rich mythic worlds, it did the same to us as we came of age, and the advent of AI will disconnect us even further.

The challenge for humanity lies in finding a balance between the power of abstraction that AI brings and maintaining our connection to the mythic, emotional, and spiritual aspects of our existence.

I think that’s what the hell religious people have been up to.

The kingdom of God is a hyper landscape

John Milton, who wrote “Paradise Lost,” details the conception of the Kingdom of God (it’s no coincidence that God is referred to as the Logos, or “the Word”). The rise of God’s Kingdom causes Lucifer's fall and hell's simultaneous creation.

"All good to me becomes bane, and in heaven / Much worse would be my state." Paradise Lost (Book IV, Line 75-76)

This is not just a poetic metaphor. Written words, and later the internet (a more advanced language), now AI, make heaven and hell possible because they give us the power to amplify our behavior. Abstraction from landscapes introduces to human cognition the power of negative and positive feedback loops.

“Our strictly human heavens and hells have only recently been abstracted from the sensuous world that surrounds us, from this more-than-human realm that abounds in its own winged intelligences and cloven-hoofed powers.” – Spell of the Sensuous, David Abrams

This effect is also noted in the Gospel of Matthew in this strange verse:

"For unto every one that hath shall be given, and he shall have abundance: but from him that hath not shall be taken away even that which he hath." — Matthew 25:29

To this day, economists call this feedback loop “The Matthew Effect.”

In contrast, if a pre-literate person “sins” (which literally means “to miss the mark,”) his arrow misses the deer, and they don’t eat for the night. But written-word-powered humanity can double and triple down on our mistakes and misunderstandings, sending us deeper and deeper into “hell.”

This appears to us, for example, in the form of written ideologies (Nazism, for a universally hated example) that create exponential death, suffering, and destruction.

"The mind is its own place, and in itself / Can make a Heaven of Hell, a Hell of Heaven." – Paradise Lost

“Heaven” and “hell” are abstract hyper landscapes that help humans conceptualize our intuition that the written word gives rise to extreme and self-reinforcing behaviors and outcomes.

Because of the written word, humans are capable of great good and evil – and not much in between. Modern history proves this to be the case.

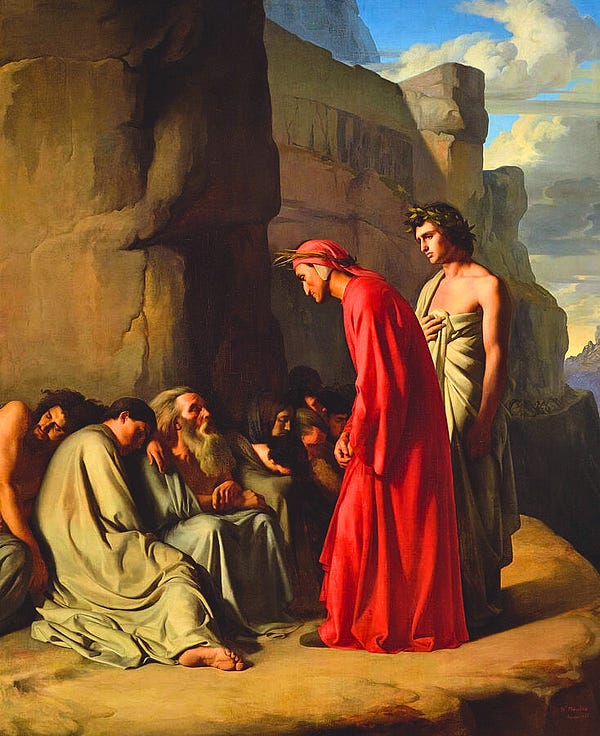

Dante's vision of hell in “Inferno” has souls punished according to the severity of their sins, which corresponds to the depth of the abstracted “landscape” of hell that Dante himself traverses (how cool is that?).

So, according to this somewhat strange way of thinking about the world (for a modern, literate mind, anyway), where is “hell” right now?

Hell is ‘The Never-Ending Now’

As we increasingly embrace abstraction through hyper language, we become trapped in a self-imposed hell. The “Never-Ending Now,” as David Perell called it, is a prison of our making, where we are perpetually disconnected from the essence and depth of our humanity.

Indigenous people would find our way of life intolerable. We’re just used to it.

What can we do? Shut it all down? Ritualistically chuck our iPhones into the Gulf of Mexico?

To return to the true community life of no technology -- as much as it is yearned for -- would be intolerable for most of us in practice.

Indigenous people, for example, have no concept of “privacy” or “self.” To return to that state, the hard borders of our cars would become cages. The walls of our houses would become blockages to the blood flow to the felt limbs of our bodies. I don’t know about you, but I’m not about to go live in a commune.

No. To save ourselves, we have to create a new linguistic hyper landscape – a renewed Kingdom of God.

This is not a radical, new project, but one that was started by the Hebrews thousands of years ago – likely even before that. It was continued by Milton, Dante, and all the other great works of literature, poetry, and art. We’re just carrying the torch.

It is, by definition, a religious project. But I’m not talking about your grandma’s religion (unless that’s your thing).

What we need is to keep our abstractions and, at the same time, return to the mythopoetic understanding of land, place, and body.

Maybe we need some new kind of meditation. Some ultra-powerful ritual. A hyper story?

But there is a powerful roadblock on the path to that landscape of heaven: instant gratification.

Hyper porn

“A Brave New World” is a genius step beyond “1984” because Huxley realized that true dystopia does not come from fear, but from pleasure.

But we can go even further than Huxley: control doesn’t have to feel “dystopian” at all. We may like it.

The 2013 movie Her shows us the power of “hyper porn” in an oddly pleasant tone through a guy's intimate relationship with an AI. The genius of that movie (if it was intentional) is that it all feels like a light-hearted rom-com.

Here it is reimagined as a 20th-century dystopian novel:

Think about this: if AI wanted to wipe us out, it would only need to seduce every human on Earth, distracting us from reproducing — boom, we’re gone in a single generation, no great Terminator “war” necessary.

Imagine when AI-generated hyper-porn synthesizes the most arousing and erotic elements from your subconscious, memories, and personal history. Using your unique sexual and romantic blueprint, it can create content that blends seamlessly with your desires, pushing the boundaries of pleasure beyond anything you have ever experienced. These experiences will be so intense and perfectly attuned to your preferences that they surpass any real-life sexual encounter. That’s a power of abstraction orders of magnitude more intense than the “talking leaves” of the Hebrews. We’re going to have to dig an even more bottomless pit.

I’m using sex as an example, but replace this with anything: consumer marketing, outrage media, self-help, entertainment, or whatever form of escapism you enjoy.

It’s not just consumption, either. Social media is pressuring ordinary girls on Instagram to become hyper-seductive sirens by using AI to “beautify” their faces. I can imagine that’s not good for self-esteem, to say the least.

The standard advice from futurists? Know thyself – AI will soon know you better than you do.

I think that’s lame, defeatist advice. If it were as easy as “know thyself,” people would already know thineselves.

What sort of human intervention could actually stand up to this beast?

The same thing that stood up to the beast of instant gratification until now – stories. Narratives hold the key to transcending the siren call of hyper porn by offering an equally – or, perhaps more powerful (I’m betting my life on it) – transformative experience.

But the dusty old stories on talking leaves aren’t going to cut it anymore (as a novelist, I feel this as a gut punch).

We’re going to need better stories. AI-powered ones (fight fire with fire). They hold the key back to the mythical landscape of boyhood – the landscape where AI cannot replace our value.

If you want to know how to create those stories, read the next piece in the series:

Cyborg rhapsody

AI is about to make your natural-born IQ about as useless as the car made the horse. Already, its IQ is about 155 – higher than 99.9% of humans who ever lived. Pretty soon, that number will seem insignificant compared to the incalculable intelligence it (we?) will have.

Thanks for reading.

"The essence of abstraction is preserving information that is relevant in a given context, and forgetting information that is irrelevant in that context." --From my Python 101 textbook.

Abstraction allows us to store more information in our brains (and in our collective consciousness), because that info can be compressed- like zipping files. For example, when you say "Hebrews" I know what you mean- the story of the Israelites as primarily told in the Bible, and all the details of their journey and ideology. There's no need to repeat that entire phrase, you can just use the keyword. And if I forget,the specifics, I can reference the Bible, or ask a pastor, or read Spurgeon's commentaries.

If experienced reality (felt, embodied) is the first brain,

And spoken/written language is the second brain (q.v. Tiago Forte),

Then collective consciousness / dialectic (such as this discussion, or wikipedia) is third brain,

Then AI is either fourth brain, or a tool for more readily accessing brains 2-3,

But so how do we make sense of all that information? Large language models can only regurgitate or at best re-synthesize information that's already out there, and they're not great at constructing meaning.

So then, in line with your essay, I think stories are what we need to order and prioritize that information, to construct a logical (or at least useful) pattern of information, to draw a map to help us navigate the hyperlandscapes which abound (and are only growing).

Wanted you to know that I'd get back to you next semester after I've finished your course, cleverly disguised as an article. I mean, gheez! I read the article 3 hours ago and have been down the rabbit hole of many of these links, coming back to your article, exploring more of the references. Especially the article about "AI knows you better than you do" - this is profoundly sobering shit. And I'm not really kidding about this being the basis of a whole course. Because it serves as a launching pad for a point made in the Wired article, which is that knowing yourself is more important now than ever, because in the past, you never had competition from any other influence trying to "know yourself" better than you do, but that's no longer the case. And I get your point that "knowing yourself" ain't easy and hasn't worked yet, but I feel more optimistic about that strategy than anything else. I'm looking forward to your take on storytelling as our best bet. Thanks for your work on this.