The Disenchantment of the Modern World Is a Myth

The ‘meaningless cosmos’ was manufactured by those who could not resolve their own contradictions.

Part 1: The Tragic Hero of the Re-enchantment

Peter Putnam was heralded as one of the greatest minds of the 20th century by thinkers like Einstein and John Wheeler. His grand theory connected the laws of physics to consciousness.1

Peter Putnam was killed by a drunk driver while riding his bike to work as a night janitor for the Department of Transportation. He lived in a one-bedroom on the edge of the swamp in Houma, Louisiana, where he watched the glimmering lights of shrimp boats nightly with his partner, Claude. Inside were thousands of typed pages of his theory, unpublished and unknown. His name did not even appear on the local news.

To understand how the scientific world could totally abandon a possible world-changing genius, we have to understand his mentor, John Wheeler.

John Wheeler was a key physicist on the Manhattan Project, working alongside Oppenheimer. He coined the terms “Black Hole” and “Wormhole.” He was also fairly certain that consciousness played a central role in the unfolding of the cosmos.

When you go out at night and happen to glimpse a star in the sky, he would explain, that photon that landed in your eye and twinkled your optic nerve, that photon could have been traveling through space since before the Great Pyramids, since before the Cambrian Explosion, only to finally find its resting place in your retina. This is where it all starts to get very strange. Because of the Laws of Relativity, which John Wheeler knew better than anyone, the photon experienced no time as it traveled through space. If we were able to see what a photon sees, we would see a universe flat in the direction of our travel. The photon “knew” since its creation that it would land in your eye that night when you happened to look up at the sky. That makes it seem like, for millions of years, it was decided that you would be born, grow up, do everything you ever did, and eventually be there to catch this flying particle (or wave) of light in your eye.

John Wheeler believed this suggested one of two things: Either the entire universe is clockwork and predictable down to the particle and you have no free will, or your consciousness somehow plays a central role in the unfolding of the cosmos.

He believed the second one. A “Participatory Universe,” he called it. His reasons were found in his emerging field of quantum theory. This theory said that the photon would either collapse into a particle or a wave, depending on how you chose to measure it. You can make a choice (ask a question) that seems to decide the quality of a thing happening in a star millions of years ago a trillion miles away.

“When you peer down into the deepest recesses of matter or at the farthest edge of the universe, you see, finally, your own puzzled face looking back at you.”2

This is a revelation on par with discovering Earth is not at the center of the cosmos. It’s even more radical, actually, because it suggests that you are, in some sense, the center of the cosmos.3

You would think this would cause an explosion of cross-domain collaboration. A literal renaissance. What does it mean, practically, that our consciousness might co-create reality? What does that suggest about psychology, free will, myth, story, poetry, theology? Is pain connected to entropy, and joy to some divine order?

The fact that you would be laughed out of academia for asking questions like that, even today, means the explosion of insight still has yet to take place. The backlash from the establishment was just as harsh as it was for Copernicus. Establishment intelligentsia benefits far too much from a poor theology of a meaningless cosmos. The power of the Atomic Age wanted to be unleashed without constraint, and a meaningless cosmos conveniently allows you to do whatever you want to it.

John Wheeler did not know this would be the reaction of the establishment. He was a man of science and perhaps naively believed the best theory would win out. He was not a student of human nature, so he failed to understand that even scientists are also subject to human blindness and arrogance.

For this same reason, he knew he would not be the one to begin to connect his physics to a unified theory of mind. But he believed his most brilliant student could. His students had a habit of making a name for themselves: Richard Feynman, to name one. He believed Peter Putnam would rock the scientific establishment and engineer a re-enchantment in the scientific world.

He was wrong. Tragically.

Peter Putnam’s Cosmos

Peter was born in a rich family in Connecticut. He was the younger brother to a handsome and athletic golden boy and himself was shy, skinny, and bookish. Peter was the sort to get punished in the Navy for reading poetry while on duty.

His mother constantly warned him that the friends he did manage to make, “only liked him for his money.” His father once did a trust-fall exercise with his brother. “Have faith and daddy will catch you!” He let the boy fall flat on his back and said, “never trust anyone, not even mommy and daddy.”

He eventually went on to study at Princeton and became the beloved student of John Wheeler. He was seen as brilliant by all of the best minds of the time, even meeting with Einstein. Robert Fuller put him with Kurt Gödel and Alan Turing as the most profound theorists of the day - the only one of the three unrecognized.

He took Wheeler’s “Participatory Universe” and created a mathematical theory of mind around it. As a jumping-off point to explain his theory, he was obsessed with the analogy of “Eddington’s Net.” It went like this:

Imagine a fisherman with a net that has two-inch holes in its weave. The fisherman would cast this net into the sea and pull up his catch. Looking at the fish, he draws two conclusions: fish have gills, and none of them are smaller than two inches. We can know for sure that the first conclusion is true, but the second one is clearly because of the net. All fish smaller than two inches, if they exist, simply slipped through the holes.

This is a crude illustration of a fundamental problem of all scientific measurement. How do you know what parts of your results are qualities of reality, and which parts are simply artifacts of your tools for measurement?

This problem turns out to be built into the fabric of the universe, because on a quantum level, the measurement can directly change the event. If you want to really understand the cosmos, then, you need a theory of the net. A theory of the measurer. A theory of the mind.

Peter wrote volumes and volumes of unpublished work on the matter. Wheeler poured over his writing, struggling to keep up with Peter’s internal logic and seemingly endless list of inverted terminology.

The basis of the theory went something like this: He believed consciousness bootstrapped itself by resolving internal contradictions. Imagine a baby who learns, in one instance, that to get milk, he needs to turn left. Then, in a different instance, he learns that to get milk, he needs to turn right. These “myths” work fine, until they eventually come into conflict. Their “horns lock.” The baby automatically becomes restless and agitated. Eventually, through sheer sensory chance, the baby discovers that a seemingly irrelevant stimulus holds the key. Turn to the warmer cheek, left or right. Synthesis.

All of our consciousness scaffolds upward like this through induction, with ever-increasing complexity. There are no algorithms. We are always in dialectic between contradictory “mythologies.” Not just during development, but in the fate of our lives, our relationships, and even the frontier of our scientific institutions. You must always pass many small odysseys into chaos, always searching for that mysterious higher synthesis.

“We know things in the act, not in their essence.” – Peter Putnam

Peter’s theory tried to show in detail, mathematically, how this played out at the level of the individual’s biological nervous system,4 all the way to the level of society and complex social structures.

This was in direct conflict with the dominant theory, which said that the universe was much more like the computer invented by Alan Turing. The Turing Cosmos looks much more like an algorithm. If you can just systematize all the inputs and outputs, you could create a unified theory of everything in the material world.

But if consciousness is fundamental, like Wheeler and his physics suggest, then this is not possible. The Turing Machine is the fisherman’s net and is not capable of encompassing within its own outputs the measurement’s effect on the results. It will always require yet-higher synthesis and as this process goes into infinity. There is no final answer.

Even Wheeler found Peter’s theory confusing. Wheeler’s daughter often watched him throw his hands up in despair working through Peter’s papers, but he kept at it. He believed that what his physics suggested made Peter’s work the necessary next step in the scientific project.

Wheeler invited Peter to speak at a conference alongside him on the subject, still truly believing that just because the most brilliant minds of the time, including him, thought that his work was important and revolutionary, so would the minds of the scientific establishment.

Wheeler’s talk was called “From Reality to Consciousness” and Peter’s was called “From Consciousness to Reality.” It was meant to be a bridge: a baton passed from one way of thinking to the next. If it had succeeded, it would have been Peter’s theory at work.

Wheeler gave his talk over, perhaps nervous or a little self-conscious or over-eager to help, he introduced Peter by saying “you’ll need a glossary to understand what he’s talking about.” Wheeler put a glossary of terms on the projector. The crowd laughed hysterically. This was not Wheeler’s intent, but the damage was done.

Peter went on stage and nervously started stammering his invented jargon. People started getting up and murmuring. The talk was cut short, and that was that.

Wheeler, a father figure to Peter, had invited him to a trust fall. Peter fell flat on his back. Never trust anyone.

At the time, his mother had been sending money to Wheeler. Wheeler turned down these bribes and insisted he wanted only to work with Peter based on the quality of his ideas. But this only reinforced a contraction in Peter’s mythology. People only like you for your money.

Peter fled academia, humiliated. He died in total obscurity in a swamp town in Louisiana while working as a janitor, despite having grown his family’s fortune to over $40 million from smart investments.

When Peter died, Wheeler said he felt he had failed to do his duty to him.

I believe he never fully understood Peter’s cosmos, and therefore didn’t understand that he couldn’t have saved him. Despite Peter’s great understanding of how it worked, even he was not able to overcome the conflicting stories he inherited from his parents. He once said, “You can’t know a person until you understand the contradiction they’re working through.” That’s how we might know Peter.

Peter was given a great conflict indeed, because I believe that if he had managed to overcome it personally, it would have dovetailed to resolving the conflict that is central to our entire society.

If Peter Putnam had succeeded in finding synthesis within himself, we might be living in a very different world. He almost undid the modern Spell of Disenchantment.

We might redeem his work if we only could pick up where he left off, and synthesize the myth of disenchantment with the nagging feeling that there is something beyond what we know.

Part 2: Fulfilling Peter’s Prophecy

When I say “myth” I don’t mean it in the modern common way of “lie” or “incorrect story.”

I also don’t mean it like Aristotle used it to mean “plot” as if it were just an entertaining tragedy.

I mean it the way Jung described it. It’s more like a dream. But not one you have at night. It is the animating principles of a person or a people. A mythos. Peter describes it fundamentally as the desire to repeat or reproduce. Everything from people to policies runs on an underlying mythos. These myths are in constant flux as they try to adapt to an ever-changing cosmos. Without new synthesis, the myths become a dogma. If you commit too hard to a dogma that is no longer in conversation with the cosmos, the entity who holds them dies.

So, when I say the “Myth” of Disenchantment I’m not saying it is a lie. It is an animating principle that was born in the West as a reaction to the atomic age. The atomic bomb (which John Wheeler helped invent) gave us the sense that we were truly masters of the cosmos. We were able to split the atom, thought to be the smallest component of reality, to create infinite energy and destruction. That discovery and its role in WWII became the Creation Myth of the modern world. Everything we have been motivated to achieve since then, from the human genome project to AI, is a result of the power of that mythos. It has influenced everything from our drop-ceiling architecture to our industrial agricultural systems.

The thorns in the side of this mythos are, among other things, the strange discoveries of quantum mechanics and the bothersome human rebellion against machine-like control. Like the baby, finding a conflict in his trusty rule of thumb of “turn right, get milk” this causes restlessness and irritability. It rejects the pain of the transformation.

So, Peter was mocked and humiliated. He was unable to resolve the conflict within himself because it was perhaps tragically tied to the fate of all of us, and we just simply weren’t ready for what he tried to say.

He was right, though, and his predictions are playing out across the scientific world. The AI project was delayed for decades because the Turing model didn’t work. Turns out you can’t model the mind with a formula of rules. The “replication crisis” shows that most of our “concrete” findings are much more a matter of subjectivity than scientists had hoped. You can’t orient a society around facts because there are an infinite number of facts, and so you first need an orienting principle, a “myth,” to tell you which facts are relevant.

Our Atomic-age mythos brought us cheap food and iPhones, so we are still mostly strong believers. It has done more good than almost all other animating principles. But that spell is ending. We no longer like phones because our age doesn’t tell us how to use them responsibly. It only tells us how to make them even more addictive.

It hurts to let go of what we thought we knew. But to me, it’s a relief to let go of the idea that I could ever draw a circle around myself that is complete.

The Danger of Trying to Draw a Circle Around Yourself

I find it strange that people aren’t more alarmed by how often the writers we most admire kill themselves.

The Myth of Disenchantment is such a powerful framework. It promises that we might eventually draw a circle around everything if we could just manage to master all the parts. In the modern era, artists also started to believe, through osmosis, that this totality of insight must apply to their domain as well. Hemingway wrote in these clean, short, legible sentences, cutting away all the “unnecessary” parts of writing - the parts our conscious mind (the Editor) can’t understand.

Without illegibility, there is no room for genuine transformation. The conflicting parts of the internal mythos are carefully destroyed, and we are starved for renewal, doubling down on what once worked but can no longer serve us.

Many modern writers followed in this tradition and tried so hard to draw a circle around themselves and their work. David Foster Wallace (one of my favorites) and Anthony Bourdain, to name just a couple. They tried to tame the wild within them. They’re good at it - they had the intelligence to create beautiful cascades of words to draw elegant circles to justify their state of being, to stave off transformation. Under the surface, the desire to transform grows so powerful that the host starts to believe that the only transformation sufficient enough to resolve their discomfort is a bodily death.

Like it or not, that is what the Myth of Disenchantment has produced. Wealth and progress on one hand, ugliness and suicide on the other.

So, how do you know if a “myth” is true or not?

You ask if it succeeds by its own measurements. The Myth of Disenchantment seeks to keep itself alive by total mastery of the material world. It’s killing itself as the need to overcome it grows. Therefore, it’s not true. Not in a final sense.

The Truth is always emerging, ever upward.

The True Story

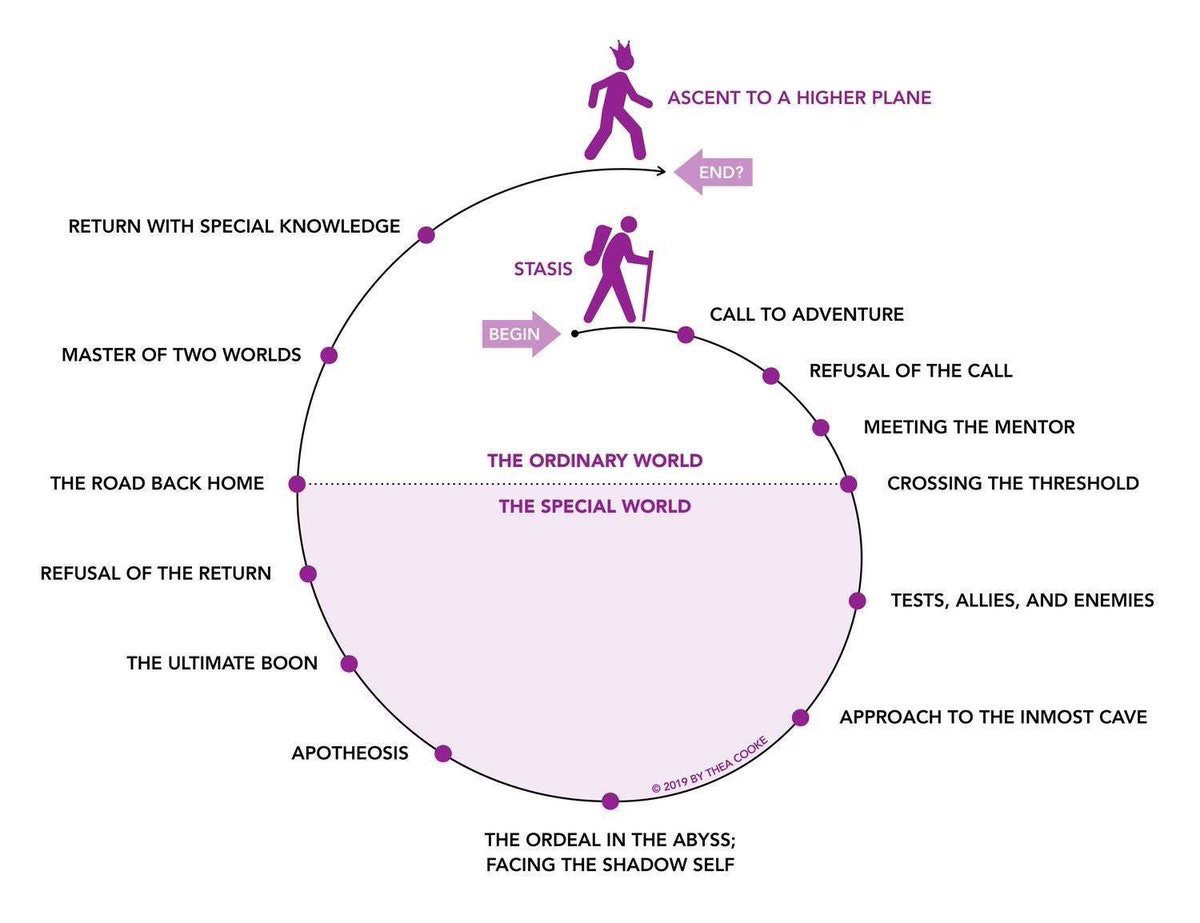

Joseph Campbell’s universal “Hero’s Journey” is another way to visualize Peter’s theory of mind (minus all the complex mathematics that tried to prove it connected to the laws of physics).

The hero starts in familiar territory, is confronted with new information, must go into the unknown, retrieve something new, and return to the beginning but with a higher synthesis.

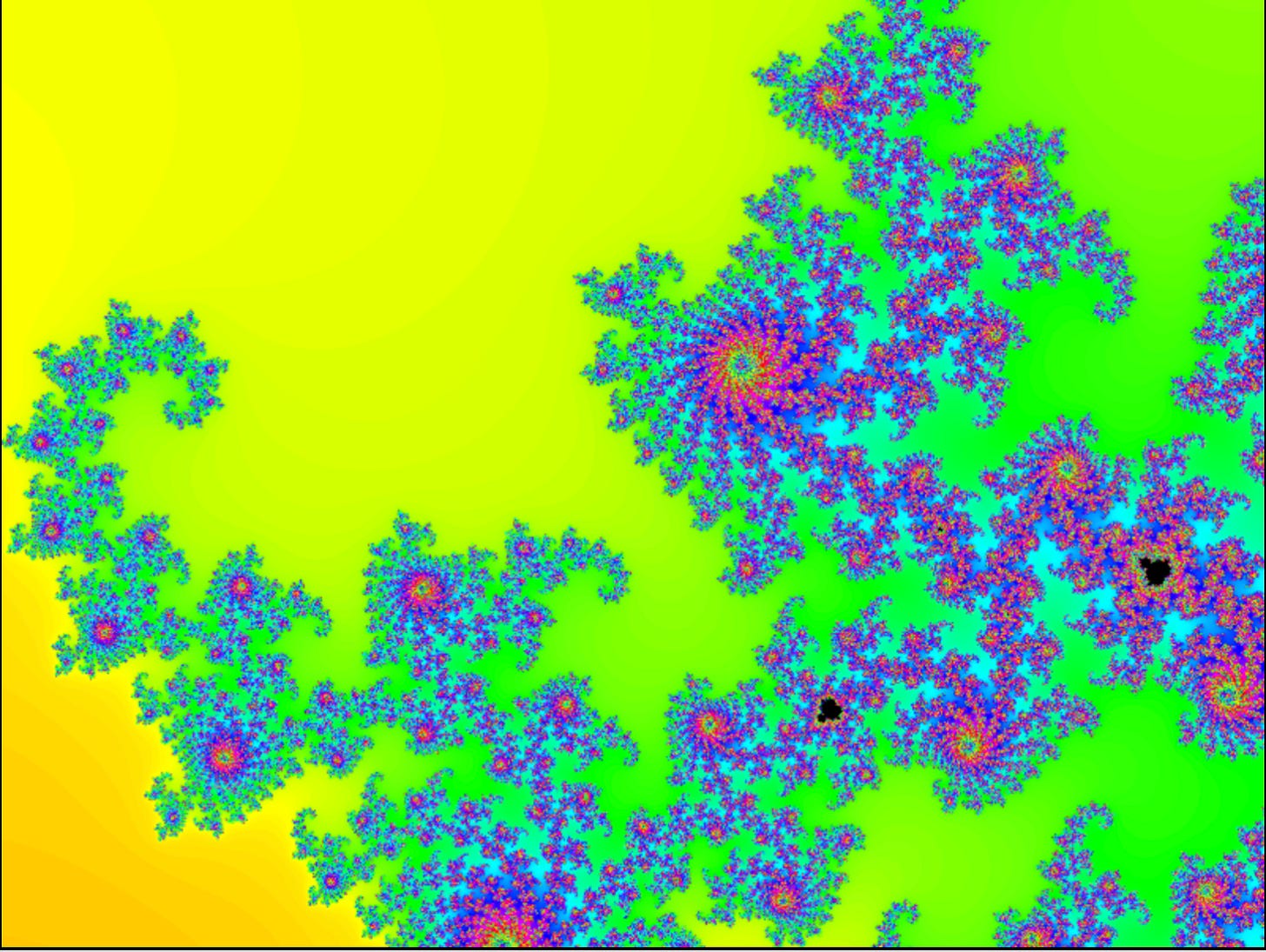

Reality is composed of these cycles, spiraling up to God and down to quarks. Our shared landscape is not a Story Circle, but more like a Hero’s Mandelbrot set.5 Every cycle of transformation is infinitely huge and infinitely small and infinitely interwoven in patterns in their endlessly unique manifestations, and yet have a shocking sense of beauty and order.

The Myth of Disenchantment is unique because it tries to flatten this ancient and universal process of transformation. It is a spell that tries to get us out of the painful descent into the unknown by claiming we know everything there is to know.

The truth is there is no escape from the pain of transformation.

The Path to Re-Enchantment

Re-enchantment won’t look like a return to some glorious past: not medieval chivalry, pagan glory, or 50s housewives. It’s not about re-casting an old spell.

It’s the simple realization that materialism is itself a spell we have cast over the world. It’s a spell, ironically, that doesn’t believe in spells, so it defeats itself by its own parameters. We do not have to rage so hard against it.

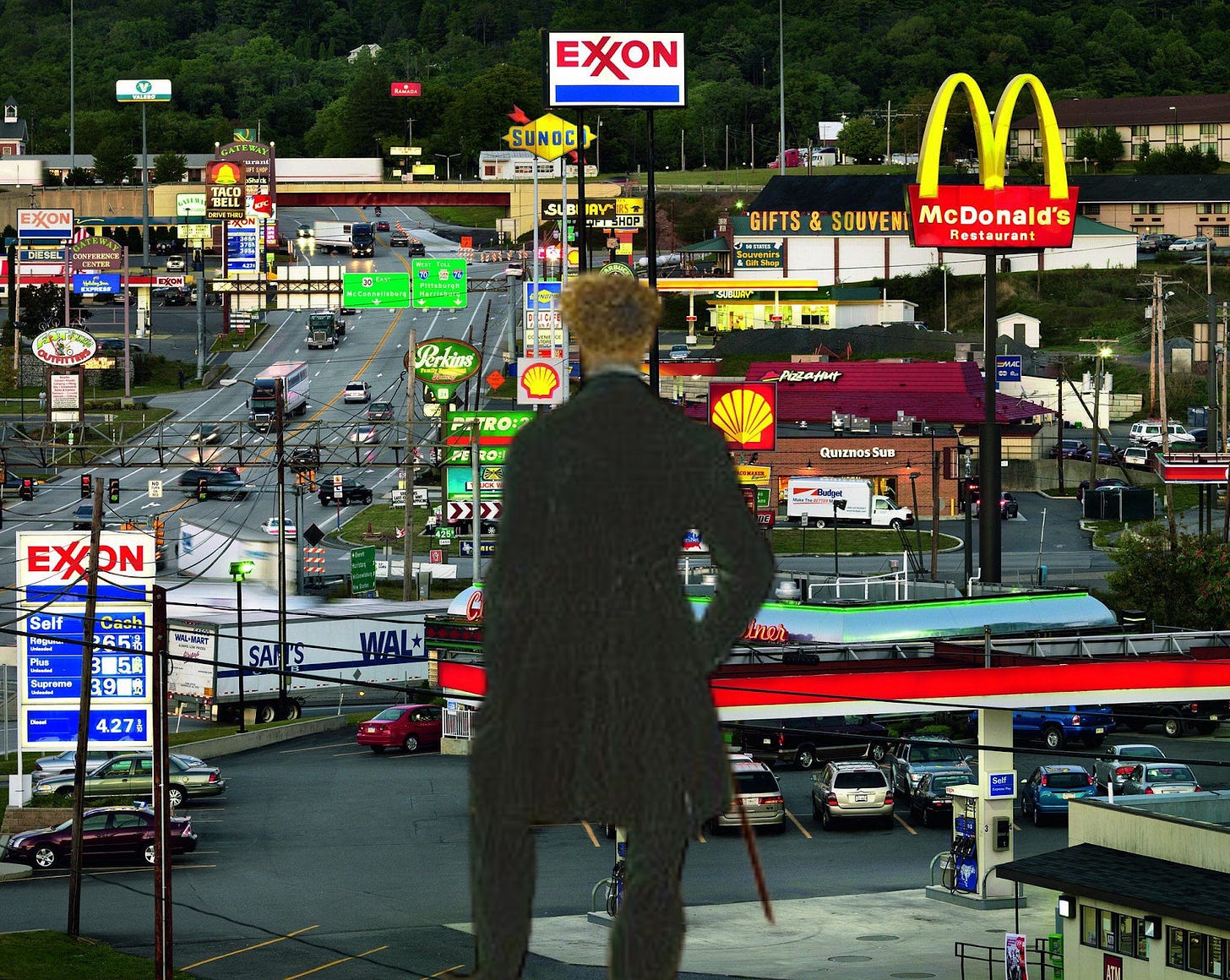

Riley and I drove to Temecula from LA to say goodbye to her uncle, who is in the final stages of ALS. It was July 4th, and as we drove back to LA, the sun setting, quiet in the car as we were feeling contemplative about our saying goodbye, suddenly the hyper-industrialized highway and suburban sprawl and corporate meaninglessness lit up with fireworks.

We turned on some 80s music and drove through the cacophony of light and sound, tears in our eyes. And what was totally clear to me was that the facade of meaninglessness that we tried to paint over the world with our McDonald's and our Shell stations and our highways plowed through the landscape, proclaiming our mastery over all things, is just that - a silly facade.

What is meaningful and what is transcendent easily rises above it, bursting like illegal fireworks, because the desire to celebrate is transcendent of the logical order. In that moment, we knew that the re-enchantment that we're all looking for here on Substack and in our personal lives is really all around us.

We have produced some ugliness with our modern pretensions, but beauty is a much more powerful force. We're much more powerful, too, when we set our eyes to contribute to that beauty and to become stewards of what's good, rather than endlessly spinning our wheels to justify the old myth that holds us back from our next transformation.

The tragedy of Peter Putnam is a sad one, but it also proves that resolving our own inner conflicts might change the entire world - the entire cosmos. That is, if Wheeler and Peter are right and our perceptions really do co-create reality.

Perhaps not all of us are fated to be so deeply connected to the destiny of mankind. But perhaps we are more than we think. Maybe if we really believed that resolving the conflict in our family system, forgiving the mistakes and cruelties of our fathers, and saying goodbye to an uncle even when it’s sad and scary, that might ripple into eternity. If we could know that for sure, we would probably take our own fate a little more seriously.

Maybe if Peter had really understood what rested on his shoulders, he would have taken the relationship with his parents a little more seriously and ended up in the history books along with Wheeler and Einstein. Maybe we wouldn’t be still talking about re-enchantment because he would have already done it.

I can only speculate. But it does encourage me to look more deeply at my own contradictions.

What contradiction are you trying to work through?

This quote is pulled (along with some of his opinions about quantum mechanics) from a profile of John Wheeler by John Horgan.

People get fired up when you make ontological claims about quantum anything. For our purposes, I’m only conveying what Wheeler thought, and suggesting that even the possibility of him being correct should have generated a lot more cross-domain interest than it did.

From Amanda Gefter’s article: “Gary Aston-Jones, head of the Brain Health Institute at Rutgers University, told me he was inspired by Putnam to go into neuroscience after Clarke gave him one of Putnam’s papers. ‘Putnam’s nervous system model presaged by decades stuff that’s very cutting edge in neuroscience,” Aston-Jones said, and yet, “in the field of neuroscience, I don’t know anybody that’s ever heard of him.’”

I think the idea that we "co-create" reality is generally right, but the way you're framing it may be backwards - at least as a corrective to that thinker (Nietzsche) whom you preface this entire essay with in the collage.

Nietzsche's statement, "God is dead," is the definitive assessment of modern disenchantment. In response to the supposed revelation of our living in a cold, meaningless universe, we must - like the deceased deity - become Creators ourselves: we must create something out of nothing, ex nihilo.

You are right to emphasize the importance of mythos for our ability to make sense out of reality, but saying we must "co-create" it keeps us stuck in the same mode that has created the dead-end we currently find ourselves in. Although it attempts to overcome the subject-object distinction, it preserves the parameters (and barriers) that separate us from the world. We remain a mind, a self, separate from the thing we are trying to understand and act upon.

To really break out of this, we must reorient ourselves to the idea that we are PARTICIPANTS in the unfolding of reality, not its creator. It is not we who exert our will upon the world (as Nietzsche posits). The world acts upon us and it is up to us to attune ourselves to it - to the demands of the moment.

I think that is likely what Putnman and Wheeler believed, and yourself as well. But the language of creation keeps us stuck in the modern mastery of nature mindset.

This doesn't quite cohere for me, which is frustrating, because it seems to be talking about something special. Your style of writing makes it seem as though something breathlessly exciting is just around the corner, but at the crucial moments it's as though you just take it for granted that we know what it is.

The first key building block seems intended to fall into place across paragraphs 5, 6 and 7 (about the photon's perception [?] of time as one instant, etc.) but it left me confused. I think the ideas and the underlying argument in those paragraphs need to be unpacked and explicated.

The same goes for the two subsections, "The Danger of Trying to Draw a Circle Around Yourself" and "The True Story". These seem to be the pivotal moments of the essay, as you marry the Wheeler/Putnam idea that consciousness is involved in the creation of reality, with the spiritual conditions and flawed cosmology of our own time. But the marriage doesn't quite happen.

I hope this doesn't seem like a disenchanted, reductive materialist sort of criticism. I am convinced that a coherent and truthful ontology must have the stream of time at its heart -- transformation, sublation, music -- and so your ideas are tantalising. But my powers of imagination and inference are pedestrian enough that a few parts of this essay seemed like non sequiturs.