The New Renaissance Will Be Techno-Rural

Stealing fire from Silicon Valley and bringing it to your home town.

Any true frontier doesn’t seem like one.

This is partly a prediction of how the New Renaissance might unfold, and partly a call to the ones obsessed with the frontier. People who left their hometowns and went to Los Angeles, hoping to make themselves into cultural demigods. Or to Silicon Valley, to build the Great Machine. Or to New York, to get rich. Or to DC for powerful shoulders to rub up on. Or to Academia to take shelter within Temple Intelligentsia.

Most of us just disappeared into the folds of Dionysian Hipsterdom - caught in local maximums of status competitions.

Those established “frontiers” are already captured. Participation in them is pretty much a pull of the lever on a slot machine. Yes, some people do succeed and their creative (and economic) output is still enormous. Survivorship bias makes success feel closer than it is. The powers that be will never fully close the door on the rags-to-riches story, because it keeps you playing. It finances their Great Machine.

I want a real frontier. That means it will not be advertised, obvious, or attractive.

The Fontenot Problem

He left every stitch of his clothes neatly folded on a stool outside the Tasty Freeze.

Fontenot is out.

If you got that call, it meant it was springtime, and that 6 '4”, 250-pound Fontenot had slipped his holds at the local insane asylum and was ripping naked through town, hollering like Tarzan.

These are real childhood memories of my dad’s best friend, a writer and a turkey call inventor named Kenny Morgan, about growing up in our hometown in the ’50s.1

The opening line: “One of the things that I see very wrong with the way things are going these days is the sovereign fact that we have lost our identity as a nation of small communities.”

All the families in town who had a switchboard would pass the message along, and pretty soon everyone in East Feliciana knew about the buck-naked wild man galumphing through Jackson.

Kenny was out hunting turkeys at the time, just a twelve-year-old boy. That’s when he saw the massive body of Fontenot sprinting toward him from across a cow field. He leapt a barbed-wire fence in a single, flat-footed bound. Kenny recalls being amazed he didn’t lose any of his “middle-aged dangling bits.”

Fontenot’s strange yodel would stir the turkeys for miles around, causing them to gobble back. Kenny made a mental note of all their locations, which he could map perfectly in his mind because he walked the land daily. He files that information away and decides to follow Fontenot on his bike.

When he finally catches up to him, he’s floating in Mr. Thompson’s pool. The entire town is there, too. Two orderlies in white coats give Fontenot a big shot of thorazine and they take him away. The town settles and clucks in Mr. Thompson’s yard, and Mrs. Thompson brings out fig preserves, biscuits, and coffee for everyone. Kenny tosses his bike in the back of Mr. Thompson’s truck and they drive him home, and Mr. Thompson comments on how gentle they are with Fontenot.

Kenny ends the letter to my dad with a lament: Governor Edwards shut down the mental hospital. The state now deals with people like Fontenot. We built more systems to deal with the inconveniences of each other’s wild humanity, we also erased any reason to get together. We believed, each step of the way, just a little more power to the abstractions (put wild ol’ Fontenot in the system, diagnose him, medicate him) and we will finally arrive somewhere good with lots of leisure time. In reality, we arrived nowhere, alone.

50 years later, during my childhood, people like Fontenot exist in a prison far away. We have systems in place. No reason to gather for anything, ever. Instead, we want a whole hell of a lot of TV. We’ve built these screens to do away with the inconvenient need to tell stories to each other.

I thought if I could get a grip on how to work that thing, things would be alright. Maybe I just wanted to capture my parents’ attention the way Seinfeld did. I don’t know. So, I crawled through the TV and ended up in LA.

The Fontenot Problem: the desire to build systems and machines to take care of inconveniences - including, and especially, each other - simultaneously does away with the meaning of life. This force is like entropy. The more technologically advanced we get, the more atomized, in general, we become.

However, there are pockets where this entropy-like force reverses. It’s almost analogous to life itself, which is a local reversal of entropy. There are times when the Fontenot Problem abates; where technology comes down from on high and gives us a new reason to come together: The shows we all watched together, the moon landing, and the friends I’ve met on Substack that I otherwise would’ve never crossed paths with.

These local reversions of the Fontenot Problem are, when taken in aggregate, the essence of renaissance.

I believe this because it has happened before.

A New Renaissance

The original Renaissance didn’t happen in the Hollywood or Silicon Valley of the 1400s (Paris, probably). It happened in a little backwater, Florence. It was dubbed “New Athens.” Patrons flocked to that dream and started investing in these weird new artist-philosopher-scientists like Da Vinci.

It all happened shortly after the arrival of the Gutenberg printing press, which distributed and democratized old texts. Otherwise illiterate frontiersmen started reading. Plato became cool again within tight communities of competing visionaries.

It reminds me a bit of the memes about Dostoevsky you see on Substack. It’s not a coincidence that after AI numbness set in, we started arguing over the importance of shrimp suffering and speculating about Kant’s potential autism. These ideas were dusty and dead when you learned them in school, but the memes make them feel alive again. That’s a literal renaissance (rebirth).

Like in the original, investors are also starting to see potential here. My friend Charlie Becker just got an investment from O’Shaughnessy Ventures2 to use AI to categorize old and odd books like the ones in his family bookstore. He’s in Houston, by the way, not in one of these cultural centers. One of many.

Institutional writers are leaving The Atlantic and The New York Times - these centralized powers of knowledge - and coming to Substack, where they can build their own audience and have some independence. No editors, no gatekeepers.

Hollywood, the music industry, and traditional publishing all seem to be committing slow suicide by refusing to invest in new IP.3 Some people see this as a sign of overall cultural collapse. That soon we’ll all just be Neurolinking forty hyper-memes per second into our brain stem. A lot of people are addicted to TikTok, I know, but in real life, I like books and movies. So do my friends. People still mostly like long-form,4 despite what they tell you.

Maybe there will be a cultural collapse. But it’s only a catastrophe for the established winners of the old frontier. For new frontier people, that just presents an opportunity to found our New Florence. Recently, I worked with some AI founders in film. It seems clear to me just from looking at their tools that it’s soon going to be possible to produce a studio-level movie with just a couple of your friends.

They don’t want you to notice that we no longer have to sacrifice our families and our land and our sanity to migrate to these cities to take part in the great cultural frontier. We can do it from our homestead.5

AI has the potential to be like the printing press was to Florence - distributing not just knowledge this time, but intelligence and craft.

There also seems to be a huge problem with this theory. AI seems to mostly produce slop.

Slop and The Illusion of Craft

At this point, if I clock that a photo or a piece of writing is AI-generated, I instantly hate it.

AI could, theoretically, improve our craft to incredible heights by removing the gatekeepers of both technical skill and politics, freeing creatives to do what they do best. I have a friend who uses AI to help her generate difficult-to-imagine landscapes in a VR headset. She finds the vista she likes and then paints it by hand or builds it into a real-life exhibit.

Mostly, though, we aren’t using it for that. Mostly, it just reveals that we would rather be seen as creative than actually risk doing it. Mostly, we fall to the level of laziness our tools allow, rather than rise to the craft they enable. According to a study, GPT increases something they’re calling “cognitive debt.”6 It’s making us stupid, I take it.

This problem is as old as dirt. When reading became popular (the AI of ancient Greece), Socrates complained that nobody would learn anything important. He was right. Too much reading makes you dumb, all things being equal. When you read what someone else wrote, you tend to think you earned that knowledge. You did not. Socrates thought it was important to speak to real people, ask them questions, and wrestle with their ideas where the stakes are high and reputations are on the line. Wisdom not earned in this way turns the mind to slop. The incredible power of abstraction gives us the illusion that we can escape the humiliation of work.

This paradox is built in. Abstractions give us a way to understand and categorize the world, but they also stand between us and primary experience. Words, and now AI, are the flame gifted to us by gods: HANDLE WITH CARE.

I read that oh-so-scary AI 2027 paper,7 predicting the apocalypse in a couple of years. Not being an “expert,” I can’t vouch for that idea one way or the other. However, I do know that experts are famously terrible at predicting the future.8 To me, it reads like breathless science fiction of Silicon Valley elites who have confused abstractions for reality. Their intricate charts and animations dazzle away incredulity. The central pathway to save the world, for them, is in solving a grand “alignment problem:” the machines need to be carefully calibrated to our values or they will turn everything into paperclips or something.

To me, cramming the right “values” into LLMs seems about as effective as an ethics class would be on a school shooter. If the past is still anything to learn from, it’s much more about each of us taking the time to align our craft and our embodied care for each other alongside the ever-increasing power of our abstractions. That manifests as undeniable beauty, which is the only true “alignment” that matters or is even possible. That beauty then might spread to others and attract them to our pockets of New Florence.

They don’t want you to think this. What they’d prefer you think is that their tools are going to be the tools to end all tools and even tool users. That’s just good marketing from Silicon Valley, true or not.

Probably, truth is, AI or even the apocalypse is not coming to save you from your toil. What you do really really matters. Abstractions like AI are clumsy titans that have to be wrestled down to the earth by a very tiny minority of people with great character.

We need periods of going back to the woods: to work for sustenance and to figure out what we actually know, like Henry David Thoreau did in writing Walden. After he did all that, perhaps ironically, he took advantage of the then-cutting-edge publishing infrastructure to distribute his hard-earned wisdom to millions.

Which brings me to the opportunity of our lifetime.

Cyborg Rhapsode

We might be like Henry, go back to the woods, and then write the book of our age. Or be like Walt, go to the western desert, and use the latest animation technology to start an empire of dreams. I think it’s a good reminder, by the way, that everyone thought that Disney’s idea was dumb and his animation technology was low-brow slop - a fad that was harming the minds of our children.

That’s remarkably similar to our sentiments about AI. But that doesn’t mean we can mimic Disney by sticking AI into his dreams. The dreams of Henry and Walt are old, full of parasites, and can no longer sustain new life. You (probably) can’t write the next great American book and you (probably) can’t make it as an actor in Hollywood. You definitely can’t do those things with the help of AI. We have to be willing to go where others aren’t looking yet.

There is a new frontier. This time, it’s not in the Western frontier, it’s in the abandoned Middle Places. If we refill these Middle Places with new stories and, like Prometheus, steal technology from up-high and bring it down to earth, we can become, in our lifetime, Cyborg Rhapsodes.

Maybe the earliest example of a proto-cyborg rhapsode was the epic writer, Homer. Long before he went pen to paper, rhapsodes (wandering storytellers) walked around Greece with these entire epics memorized. There was not yet a written language to capture them. Instead, they would use rhythm, repetition, rhyme, and locations on the landscape to map the entire stories in their heads (like how you can memorize long lists of random numbers by using “memory palaces.”) Then Homer, himself maybe one of these wandering rhapsodes, took the emerging power of the written word and transferred the story to the page. That is where he still lives, immortal. He is a cyborg (technology-integrated) rhapsode (primary experience and embodiment master).

Another example: folk songs emerged from the Appalachian Mountains with no single writer or version. House of the Rising Sun, for example, would change and alter the lyrics based on the crowd’s interest, focusing on the images of New Orleans-as-hell that went beyond conscious understanding. Then, in 1933, a man took the song he had heard his grandfather sing and recorded it to be played across the country on the emerging technology of radio.

Rick Rubin says that art is about taking a primary vision (embodied experience) and translating that into whatever technology that’s emerging: music, writing, a movie, etc. The translation is always imperfect. So it’s important not to be discouraged by our clumsy attempts. It’s also important to not confuse the abstractions for primary experience. That’s the definition of a hack - a person who just moves abstractions around like legos.

A Cyborg Rhapsode isn’t just an artist who uses AI. It’s the rare ability to be fully and recklessly immersed in the ancient and unchanging embodied experience of creation and the wherewithal to remember to capture it before it flutters away. Usually, these states of being destroy each other: you have to choose between a hack or a starving artist. Occasionally, though, they harmonize.

The first draft of this essay was written by hand. I hate writing by hand. I can’t even write in cursive anymore. But it allows me to embody the text down to the sinew in my fingers. Then I used ChatGPT to transfer the handwriting to text (impressively, GPT can parse my scrawl).

I also walk for miles around LA, listening to books and occasionally taking an AI-transcribed voice note. We were campfire storytellers long before we could read or write, so listening and speaking is even more primal than reading, deeper in the bones and closer to intuition. AI allows me to listen to stories without elders and transcribe my voice without scribes. Reading physical books adds an extra layer of embodiment by associating ideas with their location on the page, and I can quickly capture notes and highlights, again with GPT.

Always that balance: Feet in the dirt, head in the stars.

Frontier in a Graveyard

I took Riley home to Louisiana to meet the parents.

I got to see where I came from from her eyes, which was fun. She was enchanted.

While driving to show her where we used to cross the Mississippi to see Granny and Paw Paw, we stumbled on a 200-year-old church. Inside, light from the afternoon sun cut beautiful beams on the old wood and stone. Outside, the old bricks were covered in moss, and there was a sprawling graveyard.

We stood together in total silence, our legs being devoured by mosquitos, as we read the stories of people who had lived and died two centuries back. One stone said that a husband died 50 years before his wife, but she never remarried. She was buried right next to him, together for eternity. The first pastor was buried there, one of the settlers from the late 1800s. He had dreams about how the church would help the people recover from the Civil War. I could tell people adored him.

This graveyard of hopes and dreams is the topsoil of our shared culture, our “hyperlandscape.”9 Any good farmer knows that wherever there is a lot of death and decay, there is also new life. There we stood, looking at these ghosts, shocked by their aliveness.

We extracted all our embodied stories from these places, out to the desert: a sterile place of little history - a blank slate onto which we projected our cultural myths. For a hundred years, though, we’ve been trying to keep the Cyborg and lose the Rhapsode, and it means almost every successful movie now is a sequel or a remake of a 50+-year-old franchise.

Incredible amounts of creative energy are being wasted by young people trying to break into Hollywood or Silicon Valley, where they are not even wanted. We could stop wasting it on their dying dream and instead use our energy to bring those ghosts out of the grave, with near-magical technology integrated into our bones.

When we flew back to LA after visiting Louisiana, our shoulders shot up to our ears and didn’t go back down. But LA is where our work is. Riley is an actress. She’d just filmed a pretty big movie. We love storytelling. So we tried to suppress the feeling.

Growing up, my father and I used to flip houses together. For ten years, I’ve had this recurring dream (I mean the ones you have while sleeping) about finishing my father’s house.10 When we landed in LA, those dreams returned; literally every night after we came back. In them, we were rebuilding the floors, strengthening the walls, and draining floodwater.

When I mentioned this to Riley, she went quiet.

Later, I called my dad just to talk. But after we hung up, he called me back and said he’d be willing to sell me the house at a great price. Just if I ever wanted it.

What if we moved back? What if we eventually filmed in Louisiana, took advantage of the best tax breaks in the country, and used these new AI tools? We could invite our filmmaker friends, when the time was right.

And then we started hearing similar stories. People in LA with homes in Montana, Texas, Louisiana. Work is both drying up here and becoming more remote. Every single person we talked to said the same thing: “You should do it.”

I’m not suggesting we all move to Jackson, Louisiana, and go turkey hunting with the locals and then make a movie about it. But I do believe there’s a broader shift happening. People are leaving the old cultural centers. Places like Austin have already become new comedy and culture hubs.

But the goal isn’t to predict the next major center. I don’t think there will be one cultural capital anymore. Not in a physical city, anyway.

For a lot of us, the reason we left small towns behind in the first place was to find like-minded people. To that end, I have met people on Substack11 who align with me in ways I’ve never experienced before. Cities used to have a monopoly on that diversity of thought. But that age is ending. Now the most diverse space isn’t the city, it’s online. Even the best education in the world is decentralized now, if you’re willing to rethink what school should look like.12

The abstractors have overplayed their hand. They’ve made the abstraction so abstract that we don’t need to stay in their cities or consume their myths anymore. They have made an error in their greed for more and more powerful abstractions (and they know it, too, because they hate remote work,13 despite it being better for everyone involved). They’re afraid we will steal their fire and go home to rebuild. We can only do that well if we have the vision to see it as a victory rather than a regression.

It’s not about being a Luddite. It’s not even about small towns, specifically. It’s noticing the cultural “vibe shift” toward “New Romanticism,”14 and actually doing something radical about it.

100 Years from Now

A frontier never seems obvious when it’s real.

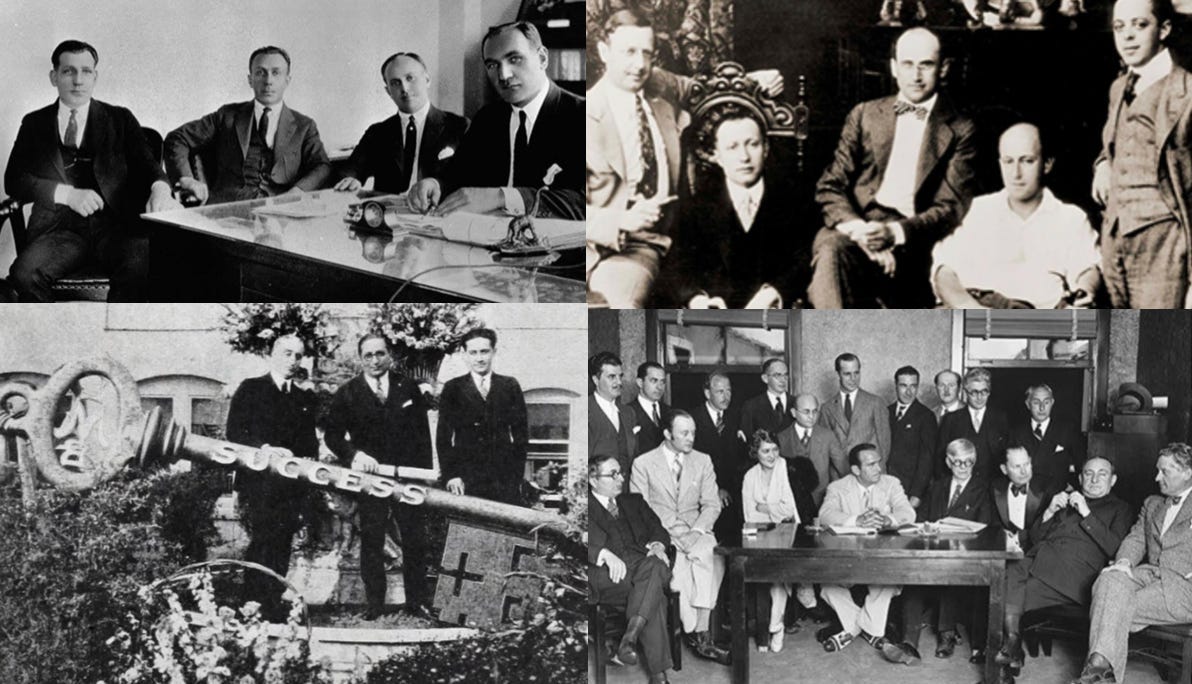

Look at these photos of the founders of Hollywood a hundred years ago.15

We forget how much it looked like a bad bet at the time. A bunch of Vaudevillians with nothing but a song in their heart went to make a movie-making empire in the desert, where there wasn’t even enough water yet to support a city. Now, it seems as inevitable as the tide.

We now have the same chance to place that bet, on the new frontier. The fact that it seems odd or difficult from the outside is exactly why it’s an actual frontier, not just the flashy facade of an old one. Going back to Middle Places won’t magically solve your problems. If you love the energy of New York and have a great community, stay there.

For the frontier people who aren’t satisfied with that: Find your abandoned middle. Learn about its ghosts. Master the technology you need to master and don’t let it master you. Then make something only you could make, that would go to the grave with you if you didn’t make it. Go build your New Florence in the forgotten places.

Steal fire from the gods and become a Cyborg Rhapsode, with coffee and fig preserves. 100 years from now, maybe they’ll look at pictures of you and say, “There were there at the beginning.”

One of the many interesting creative investments by The OSVerse. Cosmos Institute is doing something similar.

Big music studios, for example, are spending billions to acquire old music, and almost none on rising artists. Ted Gioia writes about why this is happening across the creative world.

Audience behavioral insights show we still love long-form the most.

The Free Press ran a piece about how more and more highly educated people are leaving cities to grow their own food in small towns.

Using GPT to craft an essay (which I’m not doing here) seems to make it easier in the short-term but costs the user the ability to think in the long term.

An incredibly well-produced paper by some high-ups in the AI world which basically predicts the end of the world by 2027 via superintelligent AI agents starting a shadow war with China’s AI.

One of many similar studies that suggest expertise actually makes you worse at predicting outcomes in a particular field than a layperson.

My other essay “I Want to be a Hero” defines the original term “hyperlandscape” in more detail.

Henrik Karlsson wrote a piece called “Relationships are co-evolutionary loops,” in part about he and his wife’s decision to buy his grandparents house in a small town, giving up his dreams of living in a place like New York.

In Louisiana, we found a classical education center called Sequitur. They go from 8 to noon 4 days a week, learning to read the classics in Latin and Greek. The kids’ ACT scores are fully 12 points above the national average.

Here is just one example of many of these strange articles calling for the end of remote work, despite it improving quality of life, reducing road traffic, and not impacting productivity.

Gioia argues that we’re entering a cultural era similar to the early 1800s Romantic movement, a backlash against cold rationalism and mechanistic thinking. Similar to my New Renaissance argument, he predicts a new wave of creators today will reject algorithmic culture, tech dominance, and emotionless efficiency in favor of beauty, emotion, nature, and spiritual depth.

I got this photo and idea from Will Mannon, co-founder of Write of Passage and founder of Act Two.

Cyborg Rapsodes might take my favorite coined phrase of the year. I hope you two make the jump together and experience all the adventure that comes with going forth on the frontier.

It's been five years since my wife and I made the move and found our own little outpost. We aren't ever going back because what we came from doesn't exist. All cultural centers exist in transit. Grateful ours crossed paths. Well done with this one. Another one worth showing my great grandkids when I tell them: "Go build your New Florence in the forgotten places."

This essay is rich with wonderful ideas!

I’ll read it a couple more times before commenting further.

For now, I’ll just say I’d be happy to go through the hassle of checking my shotgun through TSA at Newark airport when it’s turkey hunting season in Jackson!